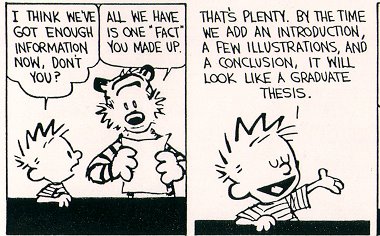

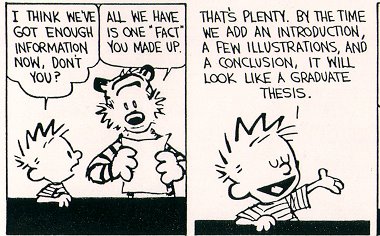

In the end, no matter the vocabulary, illustrations, drawings, and conclusions, this paper is flawed- because it is based on one fact that Calvin made up himself.

Quality, not quantity. The truth, not the carefully disguised falsehood.

With this in mind, I wish to bring to your attention an all too common trait nowadays. Namely, to authoritatively speak about ideas they know nothing about.

For your edification, I bring to you an article from the Summer 5761/ 2001 issue of

Horizons.

I have tried to find this article online, but since I cannot, I will simply reproduce it below. Please understand that is article is in no way my own, being taken or stolen by me, and is simply being used here so that I can honestly explain what it is that I find to be disingenous and intellectually dishonest about it.

The article was published under a heading titled 'Viewpoints: Perspectives on Contemporary Issues.'

Hooked on Harry: Bad for our Children!

by Chaya Brodie

I'm a third-grade teacher at a Bais Yaakov in Flatbush, and, believe it or not, at this young age my students are already hooked on Harry Potter. Initially I could not understand my coworkers' opposition toward this series. I had always enjoyed "magic stories" as a child. However, since I had not yet (and still haven't) read any of the books, I felt hesitant to voice an opinion. I'm glad I didn't. My views changed drastically after the following incident.

It began as an innocent conversation between my students about the latest H. P. book. One of my students piped up, "You know, my brother said magic isn't fake. There really is such a thing as witches."

I watched my students' reactions. Some of them oohed gleefully; others looked scared. Yet another acknowledged, "I think they live someplace in India."

What ensued was a discussion about the thrills of magic, what caused it, and how it worked. Some of the girls wanted to be witches when they grew up!

The student who had started the conversation interrupted, "Yidden can't be witches, because black magic fights Hashem. My brother said black magic is the Satan and he and Hashem fight!"

How frightening that girls should think that there is a power that can, chas v'shalom, fight Hashem. Such a belief, in a thinking adult, would be tantamount to avodah zarah (idolatry.) Due to the Harry Potter phenomenon students are walking around with grave misconceptions. Some think that magic is wonderful and acceptable. Others have strange, mixed-up notions about it. Harry Potter is validating tumah (impurity) and avodah zarah. Fundamental hashkafos (Jewish perspectives) are being warped.

I'm glad you decided to print Rabbi Orlofsky's article ("Harry Potter and the Values of the Torah Home," Horizons #27). As he mentioned, our children should not be reading about issurei d'Oraisa, By doing so we are actually instilling our children with fundamentally wrong hashkafos.

There may be teachers and parents among your readers who would be interested in knowing how I dealt with the incident. Though I am a secular studies teacher, I felt I had to address the issue. Though my students are young and some were not able to grasp all the points I made, they did come out with two strong lessons: Hashem is One and only One, and He is the Almighty. And magic is tumah and it is wrong!

I explained that Hashem gave a person the ability to choose between right and wrong so that He could reward us for our actions. Similarly, I explained that Hashem put two things into this world: kedushah (holiness) and tumah. If there were only kedushah in the world, we would have no choice but to do the right thing. Therefore, there must be an equal amount of impurity in the world. Then I stated loud and clear: Magic is preformed with kochos hatumah, and we are not allowed to practice any form of magic.

I went on to explain that previous generations were on high levels of kedushah, and therefore there was also lots of tumah in the world. As the generations grow less holy, so does the tumah get less potent in the world.

I also explained that nothing can fight against Hashem. That is an integral part of our belief, as we say each day: "Shema Yisrael Hashem Elokeinu Hashem Echad." This discussion could have been carried further, of course, but there is a limit to a third-grader's capacity for understanding.

Once again, parents, our children should not be reading these books. And, teachers, we have a responsibility to set our students straight should we find that they are mixing up the world of holiness with the world of Harry.

The author is using a pseudonym.

Before I discuss the actual statements the author is making, I want to draw your attention to the most important flaw in the entire argument. I couldn't believe it when I read it. I reread the article, and then reread it again, and was shocked by the fact that this was actually published.

"However,

since I had not yet (and still haven't) read any of the books, I felt hesitant to voice an opinion. I'm glad I didn't. My views changed drastically after the following incident."

Did I read this correctly?

This entire argument is based on the premise that the Harry Potter series is full of

tumah, ideas that are forbidden and awful. That Harry Potter corrupts children. That it is antithetical to Judaism, especially Orthodox Judaism. That it spreads notions that are simply wrong.

And the author of this entire article- the author who claims the book is wickedness in written form-

has not even read the series.Tell me, where does one get the authority to speak/ read/ write,

especially if it is to write in a condemnatory fashion, when one hasn't even

read the books? What reservoir of knowledge have you drawn upon? Where have you found your information? On what do you base this argument?

Wait- let me see if I understand-

This entire inflammatory, condemnatory reaction is based on

one class's reaction. Because one

third-grade class took the book to mean that witchcraft and wizardry might be appealing and entertaining, this means that we can infer this book is bad in and of itself. No Jewish children should or can read it! Corruption! Woe! Terror! Magic! Generalizations rule all high and mighty, let us bow to them.

I hope that you can appreciate how thoroughly ridiculous this argument is.

Unfortunately, it is not seen as being ridiculous. This idea is used in many Jewish highschools, and specifically at Templars.

People who are wholly unqualified, who have not read the books in question, or do not understand the subject matter presented, have no shame when it comes to postulating and theorizing about these ideas. Indeed, they even

admit they are uninformed, lest it seem as though they were tainted by the ideas they deplore.

Where is the logic? I see none.

I have formerly presented an example of this in terms of the idea of

Seventeen magazines. But let us spread this further. Templars is of the persuasion that everything on television, any and every movie, the Internet itself- in other words, anything that encourages open thought- is bad for the soul.

This totally negates the idea of free will and free choice.

We are not sponges. We are sieves. We all have the ability and/or capability to sift the good from the bad, the wheat from the chaff, the pomegranate seeds from the pomegranate (R' Meir reference.) I

choose what affects me. Anyone who claims that "you are affected by what you see/ read no matter what," is being absolutely and totally intellectually dishonest. Who rules you? Do you rule yourself and your mind, or do your passions rule you? If I rule myself, then I have the ability to

choose what to think about, how to understand different ideas, how what I read and see impacts me. This may be difficult, especially initially, at the first stage of thought- which is simply intake, before the processing and assimilation- but it is hardly impossible.

I am in command, not some outside entity that

forces me to think or to take ideas in certain ways. This is

my life,

my mind, and

my thoughts. People cannot be made to think in specific ways, especially when it comes to a book.

Shakespeare stated, "Nothing is either good or bad, but thinking makes it so."

In this instance, this is entirely applicable. The motivation, the intent, and the thoughts themselves are not what is wicked and bad, it is, as all things are, the way in which one understands these ideas, and moreover, the

fear many people harbor against them.

Let's discuss the main gist of this woman's argument- namely, that magic is bad, Harry Potter talks about magic, hence Harry Potter is bad.

Before we make this leap of judgement, it would certainly be correct to actually explore some of the sources where witchcraft and sorcery is mentioned in Tanakh. To understand what the Tanakh determines to be witchcraft and sorcery as opposed to what J.K. Rowling innocently writes about in Harry Potter.

1) From

Exodus 22:17

יז מְכַשֵּׁפָה, לֹא תְחַיֶּה.

17 Thou shalt not suffer a sorceress to live.

2) From

Leviticus 19:31

אַל-תִּפְנוּ אֶל-הָאֹבֹת וְאֶל-הַיִּדְּעֹנִים, אַל-תְּבַקְשׁוּ לְטָמְאָה בָהֶם: אֲנִי, יְהוָה אֱלֹהֵיכֶם.

31 Turn ye not unto the ghosts, nor unto familiar spirits; seek them not out, to be defiled by them: I am the LORD your God.

3) From

Leviticus 20: 6

ו וְהַנֶּפֶשׁ, אֲשֶׁר תִּפְנֶה אֶל-הָאֹבֹת וְאֶל-הַיִּדְּעֹנִים, לִזְנֹת, אַחֲרֵיהֶם--וְנָתַתִּי אֶת-פָּנַי בַּנֶּפֶשׁ הַהִוא, וְהִכְרַתִּי אֹתוֹ מִקֶּרֶב עַמּוֹ.

6 And the soul that turneth unto the ghosts, and unto the familiar spirits, to go astray after them, I will even set My face against that soul, and will cut him off from among his people.

4) From

Deut 18: 10 onwards

י לֹא-יִמָּצֵא בְךָ, מַעֲבִיר בְּנוֹ-וּבִתּוֹ בָּאֵשׁ, קֹסֵם קְסָמִים, מְעוֹנֵן וּמְנַחֵשׁ וּמְכַשֵּׁף.

10 There shall not be found among you any one that maketh his son or his daughter to pass through the fire, one that useth divination, a soothsayer, or an enchanter, or a sorcerer,

יא וְחֹבֵר, חָבֶר; וְשֹׁאֵל אוֹב וְיִדְּעֹנִי, וְדֹרֵשׁ אֶל-הַמֵּתִים.

11 or a charmer, or one that consulteth a ghost or a familiar spirit, or a necromancer

5) From

Samuel I, Chapter 28:

ה וַיַּרְא שָׁאוּל, אֶת-מַחֲנֵה פְלִשְׁתִּים; וַיִּרָא, וַיֶּחֱרַד לִבּוֹ מְאֹד.

5 And when Saul saw the host of the Philistines, he was afraid, and his heart trembled greatly.

ו וַיִּשְׁאַל שָׁאוּל בַּיהוָה, וְלֹא עָנָהוּ יְהוָה--גַּם בַּחֲלֹמוֹת גַּם בָּאוּרִים, גַּם בַּנְּבִיאִם.

6 And when Saul inquired of the LORD, the LORD answered him not, neither by dreams, nor by Urim, nor by prophets.

ז וַיֹּאמֶר שָׁאוּל לַעֲבָדָיו, בַּקְּשׁוּ-לִי אֵשֶׁת בַּעֲלַת-אוֹב, וְאֵלְכָה אֵלֶיהָ, וְאֶדְרְשָׁה-בָּהּ; וַיֹּאמְרוּ עֲבָדָיו אֵלָיו, הִנֵּה אֵשֶׁת בַּעֲלַת-אוֹב בְּעֵין דּוֹר.

7 Then said Saul unto his servants: 'Seek me a woman that divineth by a ghost, that I may go to her, and inquire of her.' And his servants said to him: 'Behold, there is a woman that divineth by a ghost at En-dor.'

ח וַיִּתְחַפֵּשׂ שָׁאוּל, וַיִּלְבַּשׁ בְּגָדִים אֲחֵרִים, וַיֵּלֶךְ הוּא וּשְׁנֵי אֲנָשִׁים עִמּוֹ, וַיָּבֹאוּ אֶל-הָאִשָּׁה לָיְלָה; וַיֹּאמֶר, קסומי- (קָסֳמִי-) נָא לִי בָּאוֹב, וְהַעֲלִי לִי, אֵת אֲשֶׁר-אֹמַר אֵלָיִךְ.

8 And Saul disguised himself, and put on other raiment, and went, he and two men with him, and they came to the woman by night; and he said: 'Divine unto me, I pray thee, by a ghost, and bring me up whomsoever I shall name unto thee.'

ט וַתֹּאמֶר הָאִשָּׁה אֵלָיו, הִנֵּה אַתָּה יָדַעְתָּ אֵת אֲשֶׁר-עָשָׂה שָׁאוּל, אֲשֶׁר הִכְרִית אֶת-הָאֹבוֹת וְאֶת-הַיִּדְּעֹנִי, מִן-הָאָרֶץ; וְלָמָה אַתָּה מִתְנַקֵּשׁ בְּנַפְשִׁי, לַהֲמִיתֵנִי.

9 And the woman said unto him: 'Behold, thou knowest what Saul hath done, how he hath cut off those that divine by a ghost or a familiar spirit out of the land; wherefore then layest thou a snare for my life, to cause me to die?'

י וַיִּשָּׁבַע לָהּ שָׁאוּל, בַּיהוָה לֵאמֹר: חַי-יְהוָה, אִם-יִקְּרֵךְ עָוֹן בַּדָּבָר הַזֶּה.

10 And Saul swore to her by the LORD, saying: 'As the LORD liveth, there shall no punishment happen to thee for this thing.'

יא וַתֹּאמֶר, הָאִשָּׁה, אֶת-מִי, אַעֲלֶה-לָּךְ; וַיֹּאמֶר, אֶת-שְׁמוּאֵל הַעֲלִי-לִי.

11 Then said the woman: 'Whom shall I bring up unto thee?' And he said: 'Bring me up Samuel.'

יב וַתֵּרֶא הָאִשָּׁה אֶת-שְׁמוּאֵל, וַתִּזְעַק בְּקוֹל גָּדוֹל; וַתֹּאמֶר הָאִשָּׁה אֶל-שָׁאוּל לֵאמֹר לָמָּה רִמִּיתָנִי, וְאַתָּה שָׁאוּל.

12 And when the woman saw Samuel, she cried with a loud voice; and the woman spoke to Saul, saying: 'Why hast thou deceived me? for thou art Saul.'

יג וַיֹּאמֶר לָהּ הַמֶּלֶךְ אַל-תִּירְאִי, כִּי מָה רָאִית; וַתֹּאמֶר הָאִשָּׁה אֶל-שָׁאוּל, אֱלֹהִים רָאִיתִי עֹלִים מִן-הָאָרֶץ.

13 And the king said unto her: 'Be not afraid; for what seest thou?' And the woman said unto Saul: 'I see a godlike being coming up out of the earth.'

In these examples, we see a recurring theme- namely, that the

practice of witchcraft is forbidden. The sorceress is not suffered to live, the one who practices the arts of necromancy, of Ov and Yidoni, is put to death. Even more telling is the response of the witch-woman to Saul, where she states, "'Behold, thou knowest what Saul hath done, how he hath cut off those that divine by a ghost or a familiar spirit out of the land; wherefore then layest thou a snare for my life, to cause me to die?" Once she actually performs the act- calls up the spirit of Samuel- it is

then that she will be held accountable, but not before- it is that

action which is considered the "snare for her life."

I would also like to point out that most of these examples describe necromancy, dealings with the dead, or if they do not, are juxtaposed to verses about Molech, where one sacrifices one's own children. This sorcery is a sorcery of death, at least in the literal sense (though Rashi goes on to expound about the various types of divination that are considered to be witchcraft.)

These examples prove that the

practice of magic is forbidden, but what of knowledge of magic?

The premise of the aforementioned author's argument is that the children should not read Harry Potter lest they encounter

tumah, wickedness and evil. Yet it is not the

knowledge of magic that is a problem, it is the actual

practice of magic. In fact, knowledge of magic was even a requirement in the times of the Sanhedrin!

R. Johanan said: None are to be appointed members of the Sanhedrin, but men of stature, wisdom, good appearance, mature age, with a knowledge of sorcery,38 and who are conversant with all the seventy languages of mankind,39 in order that the court should have no need of an interpreter.

Sanhedrin 17a

Why must these men have knowledge of sorcery? So that they are fit to judge whether the sorcerer/ sorceress in question was actually guilty of witchcraft! If they knew nothing of sorcery, what good would they be to the court?

There is another incident which makes it quite clear that the Sages were versed in sorcery/ understood witchcraft.

The sage was immediately aware of his student's question. He said, "You must realize that Shimon ben Shetach is partially to blame for the tax collector's immorality, as well as for the immorality in Ashkelon in general. There are eighty Jewish women in Ashkelon who practice black magic and engage in all sorts of disgusting rites. Shimon ben Shetach once made a vow that when he became head of the Sanhedrin, he would rid the city of them, but he has never kept his vow."

When the student awoke in the morning, the dream was still fresh in his mind. He hurried to Jerusalem, where he related it to Shimon ben Shetach. The sage realized that the message was correct, and immediately made plans to capture the eighty witches. From among his disciples, he chose eighty of the tallest and strongest men. Each one was given a large jar and a light cloak that would readily show the slightest sign of wetness.

Shimon ben Shetach chose a stormy day for his expedition. It was raining so hard that it was almost impossible to go outdoors. He instructed his men to take their cloaks and place them in the waterproof jars, closing them very tight. At his signal, they were to come into the cave, and before the witches could see them, put on their cloaks. As soon as they approached the witches, each man was to grasp a woman and lift her off the ground. The women's occult arts would be totally powerless as long as their feet were not touching the ground. Occult powers come from the earth and are only effective when one is in contact with it.

Leaving his disciples standing in the downpour, Shimon ben Shetach entered the cave of the witches. He was immediately challenged. "Who are you and what do you want?" "I am a master warlock. I have heard that you also practice the occult arts. I would like to compare notes with you." "Not so fast. Do you think that we reveal our secrets to anyone who walks in? Can you show us any evidence of your powers?" "As you can see, it is raining very hard outside. But with a word I can produce eighty young men to entertain you, and their clothes will be perfectly dry." "Now that's evidence that we would enjoy seeing. Do that, and you will be welcome."

The young men had protected themselves from the rain under an overhang adjoining the mouth of the cave, where the witches could not see them. They had changed into their dry cloaks, and at their master's signal they came dancing into the cave. Each one grabbed a witch as if to pull her into the dance, and before the women knew what was happening, they all were on the shoulders of the young men. With the witches powerless, the sage assembled a court of law and passed sentence. All eighty were immediately hanged. It was to be an object lesson to all the populace to avoid such practices in the future. ...

From this we see that anyone practicing the occult arts must stand on the bare earth in order for his practices to be effective. In the case of this plague, however, all the earth had turned into lice and vermin. The Egyptian wizards were standing on insects and not on the ground, and therefore they could not make use of their arts.

(I am unsure of the Talmudic source (I think it's Sanhedrin); I found this on Jewish Gates.)

Why is is that we cannot practice magic?

One possible answer is that we are not meant to know the future. R' Hirsch postulates:

Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch (great 19th century Torah leader in Germany) explains that one who places his faith in "the realm of dark, unfree, mysterious powers" will abandon his belief in free will. He will conclude that the moral worth of his actions have no effect on his life and his destiny, and will, therefore, become degenerate in his behavior. As Hirsch bluntly puts it, "The whole moral degeneration of the Canaanite nations came from these things, which supported and were the mainstay of immorality." (Commentary on the Torah: Deuteronomy, p. 352)

Found on this website

If we agree with this reason, or at least allow it as a possibility, then we ought to be

grateful to J.K. Rowling as opposed to voicing condemnatory views. Look at the beautiful way in which she stresses free will as opposed to an ultimate prophecy- similar to the way in which, in the Torah, we believe that a prophet's "good prophecies" ultimately come true, but if his "bad prophecies" (i.e., those that forecast sad or troubling times ahead) do not, it is not considered a problem on the part of the prophet, but rather as a good sign, namely, that the Jews have averted the prophecy through repentance. Hence free will does indeed reign triumphant...

“But Harry, never forget that what the prophecy says is only significant because Voldemort made it so. I told you this at the end of last year. Voldemort singled you out as the person who would be most dangerous to him –and in doing so, he made you the person who would be most dangerous to him!”

“But it comes to the same— ”

“No, it doesn’t!” said Dumbledore, sounding impatient now. (…) “If Voldemort had never heard of the prophecy, would it have been fulfilled? Would it have meant anything? Of course not! Do you think every prophecy in the Hall of Prophecy has been fulfilled?”

“But,” said Harry, bewildered, “but last year, you said one of us would have to kill the other –”

“Harry, Harry, only because Voldemort made a grave error, and acted on Professor Trelawney’s words [i.e., the prophecy]! If Voldemort had never murdered your father, would he have imparted in you a furious desire for revenge? Of course not! (…) Voldemort himself created his worst enemy… (…) He heard the prophecy and he leapt into action, with the result that he (…) handpicked the man most likely to finish him…” (…)

“But, sir,” said Harry, making valiant efforts not to sound argumentative, “it all comes to the same thing, doesn’t it? I’ve got to try and kill him, or—”

“Got to?” said Dumbledore. “Of course you’ve got to! But not because of the prophecy! Because you, yourself, will never rest until you’ve tried! We both know it! Imagine, please, just for a moment, that you had never heard that prophecy! How would you feel about Voldemort now? Think!” (…)

“I’d want him finished,” said Harry quietly. “And I’d want to do it.”

“Of course you would!” cried Dumbledore. “You see, the prophecy does not mean you have to do anything! (…) In other words, you are free to choose your way, quite free to turn your back on the prophecy! But Voldemort continues to set store by the prophecy. He will continue to hunt you… which makes it certain, really, that –”

“That one of us is going to end up killing the other,” said Harry. “Yes.”

But he understood at last what Dumbledore had been trying to tell him. It was, he thought, the difference between being dragged into the arena to face a battle to the death and walking into the arena with your head held high. Some people, perhaps, would say that there was little to choose between the two ways, but Dumbledore knew –and so do I, thought Harry, with a rush of fierce pride, and so did my parents –that there was all the difference in the world.

J. K. Rowling, Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince, Ch. 23, p. 512

Taken from this site

The prophecy does not commit Harry to a certain plan of action, rather, he himself chooses whether or not to face Voldemort, and whether or not to kill him. Rather than giving himself up to the hopeless "realm of dark, unfree, mysterious powers," which rule his life, Harry believes in his power to choose- free will.

Fairy tales and magic are the child's guide to the universe. It is through fairytales that a child learns about justice and injustice, good and evil, the wicked and the pure. Magic as expressed in Harry Potter, far from being wreathed in evil auras, is actually a catalyst that allows children to think. Magic is simply an element; it is the wizard's choice to use it for good or evil. Voldemort chooses to use magic in an evil way. Harry, Hermione and Ron, combat him (and suffer/ make mistakes along the way) by using magic for good.

When the little children in that woman's third-grade class said they wanted to grow up to be witches, I am extremely certain they were not referring to necromancers. How am I so certain? Because the average third-grader doesn't know what necromancy is. The concept of raising the dead doesn't occur to them. The glamour of magic- the ability to make the dishes wash themselves, to have chess pieces that move, to transform animals into cooking utensils and vice versa-

this is what attracts them, not nefarious motives. Attributing such dark ideas to innocent third-graders is to do what the teachers at Templars do so admirably- project your own mistaken thoughts/ ideas upon others.

I would also like to stress the relative confusion nowadays between the magic we associate with miraculous events during the times of the prophets as opposed to the sorcery and witchcraft the Torah opposes. To say that all magic is

tumah is to totally confuse children who read stories such as the following in the Gemara:

Solomon thereupon sent thither Benaiahu son of Jehoiada, giving him a chain on which was graven the [Divine] Name and a ring on which was graven the Name and fleeces of wool and bottles of wine. Benaiahu went and dug a pit lower down the hill and let the water flow into it13 and stopped [the hollow] With the fleeces of wool, and he then dug a pit higher up and poured the wine into it14 and then filled up the pits. He then went and sat on a tree. When Ashmedai came he examined the seal, then opened the pit and found it full of wine. He said, it is written, Wine is a mocker, strong drink a brawler, and whosoever erreth thereby is not wise,15 and it is also written, Whoredom and wine and new wine take away the understanding.16 I will not drink it. Growing thirsty, however, he could not resist, and he drank till he became drunk, and fell asleep. Benaiahu then came down and threw the chain over him and fastened it. When he awoke he began to struggle, whereupon he [Benaiahu] said, The Name of thy Master is upon thee, the Name of thy Master is upon thee. As he was bringing him along, he came to a palm tree and rubbed against it and down it came. He came to a house and knocked it down. He came to the hut of a certain widow. She came out and besought him, and he bent down so as not to touch it, thereby breaking a bone. He said, That bears out the verse, A soft tongue breaketh the bone1 He saw a blind man straying from his way and he put him on the right path. He saw a drunken man losing his way and he put him on his path. He saw a wedding procession making its way merrily and he wept. He heard a man say to a shoemaker, Make me a pair of shoes that will last seven years, and he laughed. He saw a diviner practising divinations and he laughed. When they reached Jerusalem he was not taken to see Solomon for three days. On the first day he asked, Why does the king not want to see me? They replied, Because he has overdrunk himself. So he took a brick and placed it on top of another. When they reported this to Solomon he said to them, What he meant to tell you was, Give him more to drink. On the next day he said to them, Why does the king not want to see me? They replied, Because he has over-eaten himself. He thereupon took one brick from off the other and placed it on the ground. When they reported this to Solomon, he said, He meant to tell you to keep food away from me. After three days he went in to see him. He took a reed and measured four cubits and threw it in front of him, saying, See now, when you die you will have no more than four cubits in this world. Now, however, you have subdued the whole world, yet you are not satisfied till you subdue me too. He replied: I want nothing of you. What I want is to build the Temple and I require the shamir. He said: It is not in my hands, it is in the hands of the Prince of the Sea who gives it only to the woodpecker,2 to whom he trusts it on oath. What does the bird do with it? — He takes it to a mountain where there is no cultivation and puts it on the edge of the rock which thereupon splits, and he then takes seeds from trees and brings them and throws them into the opening and things grow there. (This is what the Targum means by nagar tura).3 So they found out a woodpecker's nest with young in it, and covered it over with white glass. When the bird came it wanted to get in but could not, so it went and brought the shamir and placed it on the glass. Benaiahu thereupon gave a shout, and it dropped [the shamir] and he took it, and the bird went and committed suicide on account of its oath.

Benaiahu said to Ashmedai, Why when you saw that blind man going out of his way did you put him right? He replied: It has been proclaimed of him in heaven that he is a wholly righteous man, and that whoever does him a kindness will be worthy of the future world. And why when you saw the drunken man going out of his way did you put him right? He replied, They have proclaimed concerning him in heaven that he is wholly wicked, and I conferred a boon on him in order that he may consume [here] his share [in the future].4 Why when you saw the wedding procession did you weep? He said: The husband will die within thirty days, and she will have to wait for the brother-in-law who is still a child of thirteen years.5 Why, when you heard a man say to the shoemaker, Make me shoes to last seven years, did you laugh? He replied: That man has not seven days to live, and he wants shoes for seven years! Why when you saw that diviner divining did you laugh? He said: He was sitting on a royal treasure: he should have divined what was beneath him.

Solomon kept him with him until he had built the Temple. One day when he was alone with him, he said, it is written, He hath as it were to'afoth and re'em,6 and we explain that to'afoth means the ministering angels and re'em means the demons.7 What is your superiority over us?8 He said to him, Take the chain off me and give me your ring, and I will show you. So he took the chain off him and gave him the ring. He then swallowed him,9 and placing one wing on the earth and one on the sky he hurled him four hundred parasangs. In reference to that incident Solomon said, What profit is there to a man in all his labour wherein he laboureth under the sun.10

And this was my portion from all my labour.11 What is referred to by 'this'? — Rab and Samuel gave different answers, one saying that it meant his staff and the other that it meant his apron.12 He used to go round begging, saying wherever he went, I Koheleth was king over Israel in Jerusalem.13 When he came to the Sanhedrin, the Rabbis said: Let us see, a madman does not stick to one thing only.14 What is the meaning of this? They asked Benaiahu, Does the king send for you? He replied, No. They sent to the queens saying, Does the king visit you? They sent back word, Yes, he does. They then sent to them to say, Examine his leg.15 They sent back to say, He comes in stockings, and he visits them in the time of their separation and he also calls for Bathsheba his mother. They then sent for Solomon and gave him the chain and the ring on which the Name was engraved. When he went in, Ashmedai on catching sight of him flew away, but he remained in fear of him, therefore is it written, Behold it is the litter of Solomon, threescore mighty met, are about it of the mighty men of Israel. They all handle the sword and are expert in war, every man hath his sword upon his thigh because of fear in the night.16

Rab and Samuel differed [about Solomon]. One said that Solomon was first a king and then a commoner,17 and the other that he was first a king and then a commoner and then a king again.

Gittin 68a and b

Solomon captures Asmadei, the King of Demons, through the use of a chain engraved with the Divine Name? Solomon looses Asmadei, and Asmadei ousts him from his position of power, throwing him 400 parsangs and seizing the crown in Solomon's absence? Asmadei has the clawed, webbed feet of a chicken, and hence has relations with Solomon's wives in his stockings? Asmadei visits women during their time of the month, and moreover calls for Bathsheba? Solomon has the power to recapture Solomon with the golden chain?

Do you know what this reminds me of? A Russian fairytale that is exceedingly similar- in fact, this idea is prevalent across the entire genre- namely,

"Koshchei the Deathless."Look at what happens by Solomon:

Solomon kept him with him until he had built the Temple. One day when he was alone with him, he said, it is written, He hath as it were to'afoth and re'em,6 and we explain that to'afoth means the ministering angels and re'em means the demons.7 What is your superiority over us?8 He said to him, Take the chain off me and give me your ring, and I will show you. So he took the chain off him and gave him the ring. He then swallowed him,9 and placing one wing on the earth and one on the sky he hurled him four hundred parasangs. In reference to that incident Solomon said, What profit is there to a man in all his labour wherein he laboureth under the sun.10

Now look at what happens by Prince Ivan:

He couldn't help doing so. The moment Marya Morevna had gone he rushed to the closet, pulled open the door, and looked in-- there hung Koshchei the Deathless, fettered by twelve chains. Then Koshchei entreated Prince Ivan, saying:

`Have pity upon me and give me to drink! Ten years long have I been here in torment, neither eating nor drinking; my throat is utterly dried up.'

The Prince gave him a bucketful of water; he drank it up and asked for more, saying:

`A single bucket of water will not quench my thirst; give me more!'

The Prince gave him a second bucketful. Koshchei drank it up and asked for a third, and when he had swallowed the third bucketful, he regained his former strength, gave his chains a shake, and broke all twelve at once.

`Thanks, Prince Ivan!' cried Koshchei the Deathless, `now you will sooner see your own ears than Marya Morevna!' and out of the window he flew in the shape of a terrible whirlwind. And he came up with the fair Princess Marya Morevna as she was going her way, laid hold of her and carried her off home with him. But Prince Ivan wept full sore, and he arrayed himself and set out a- wandering, saying to himself, `Whatever happens, I will go and look for Marya Morevna!'

In both cases, the Prince/ Warrior sets loose his greatest enemy, and suffers because of it- Solomon because he himself is replaced on the throne and becomes a commoner, Ivan because Marya is stolen away from him. In both places, it is curiousity that is their downfall- Solomon because he wishes the answer to a question, Ivan because Marya has forbidden him to enter that specific room. This idea is one carried across many traditions, occurring specifically in the Arabian Nights, for instance.

The difference between these two scenarios? Very little. However, one is considered a magical fairy tale, the other one is the truth according to the Gemara.

This is yet another reason that one cannot be so quick to dismiss worlds like those of J.R.R. Tolkien, J.K. Rowling and Diana Wynne Jones. These authors succeed in allowing us into a realm of magic, a place that is both beautiful and terrible, where there are the wicked and the kind, humanity in a different form. One cannot write off magic as being evil in and of itself; rather, it is a tool- something which can be used for evil or for good.

The Torah distinguishes between sorcery/ witchcraft and miracles, which to us (especially nowadays) certainly

seem like magic. Splitting the red sea? Water from a rock? These are miracles, but in our world, they too exist under the subheading "magic." Sorcery, on the other hand, is continously linked with necromancy. According to the series 'The Midrash Says,' Laban used terafim, which was really the oiled skull of a human child, to communicate with the dead. We have a specific example, in the form of the Witch of Endor, of witches calling upon the dead. But there is another kind of "magic," as we would think of it nowadays- the magic of God. The Urim Vetumim, which was animated by a scroll containing the special name of God, and which operated through illuminating the particular letters (out of the tribes' names) that provided the answer. The ability of God to rain manna down upon the Jews, according to the Midrash, manna that was mixed with jewels. This is not considered magic by the Torah/ Tanakh, but

nowadays the word is used interchangeably, and refers to everything that is out of the ordinary/ miraculous/ unpredictable.

Indeed, the Merriam-Webster

definition is:

Main Entry: 1mag·ic Pronunciation: 'ma-jikFunction: nounEtymology: Middle English magique, from Middle French, from Latin magice, from Greek magikE, feminine of magikos Magian, magical, from magos magus, sorcerer, of Iranian origin; akin to Old Persian magus sorcerer

1 a : the use of means (as charms or spells) believed to have supernatural power over natural forces b : magic rites or incantations

2 a : an extraordinary power or influence seemingly from a supernatural source b : something that seems to cast a spell : ENCHANTMENT

3 : the art of producing illusions by sleight of hand

Definition number one seems to be the definition of the sorcery/ magic discussed in Tanakh, where human influence is required. Definition number two, however, could certainly be used to describe God- is He not a supernatural source?

The concern of the teacher- to worry that children may mix up the "world of holiness with the world of Harry" is totally unfounded. Our Torah and Tanakh is

filled with colorful, rich references to miraculous and magical occurences. When innocent third-graders discuss the powers of magic, they refer to the thrills of flying on brooms, waving wands amidst shining sparks, looking at photographs that move, or immobilizing people with one word-

not the idea of forcing their brother or sister to walk through fire, or calling down the dead. Even in books that discuss magic, calling down the dead is an unfavorable practice.

Sabriel, by Garth Nix, is the one that most stresses this idea, but J.K. Rowling's

Inferi, and Lloyd Anderson's

Cauldron-Born are certainly disturbing as well. Although this is different from the Tanakh's treatment of the subject, where Samuel asks why Saul disturbs his rest, it accomplishes the same effect- distaste for the idea of raising the dead.

The idea of magic- if presented correctly- is not a hinderance to Judaism, but rather an

asset. It is through close observation of various stories and tales from Tanakh and the Torah that I am able to notice the myriads of allusions, ideas, and stories that are based on them or are similar to them. Magic allows children to enter a world of imagination, enjoy themselves, think creatively, and still understand the difference between good and evil- in this case, between Harry and Voldemort. Good and evil are very similar, even as Harry and Voldemort are; there is a thin line that separates them, and that is their choices- similar to the (albeit physical) idea that, "There is but a hair's-breadth between Gan Eden and 'Gehinnom." (Source

here)

Magic,

especially Harry Potter, is essential for children. My brothers have learned so much from J. K. Rowling- her series has caused an interest in so much more than magic. Magic is attractive in that it is glamorous, but it is the eventual faceoff between Harry and Voldemort that is of the most interest. To prevent children from reading these books on the basis that magic has the ability to taint them is to completely forbid them access to the ideas encased in our own Torah, tradition and Gemara. For it is not as though Harry advocates killing, murder, Molech, necromancy and beastiality- he is the very antithesis to/of this! Harry also demonstrates the fact that no matter the predictions made about you, the prophecies people have stated- it is free will and choice that rules.

In a very, very entertaining twist (especially in light of the woman's argument), Firenze (a centaur who acts as Divination teacher) spends his time teaching the class that even centaurs (who are most skilled in this area) can misread the signs in the stars, and that, moreover, the whole idea is a very shaky business.

It was the most unusual lesson Harry had ever attended. They did indeed burn sage and mallowsweet there on the classroom floor, and Firenze told them to look for certain shapes and symbols in the pungent fumes, but he seemed perfectly unconcerned that not one of them could see any of the signs he described, telling them that humans were hardly ever good at this, that it took centaurs years and years to become competent, and finished by telling them that it was foolish to put too much faith in such things anyway, because even centaurs sometimes read them wrongly. He was nothing like any human teacher Harry had ever had. His priority did not seem to be to teach them what he knew, but rather to impress upon them that nothing, not even centaurs' knowledge, was foolproof.

'Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix, Chapter 27, Page 603

This completely conforms with the Judaic idea that one's fate (although it is arguable whether this refers to all or only Jews) is not predestined or written in the stars...remember the incident with the snake?

From Samuel too [we learn that] Israel is immune from planetary influence. For Samuel and Ablat were sitting, while certain people were going to a lake.5 Said Ablat6 to Samuel: 'That man is going but will not return, [for] a snake will bite him and he will die.' 'If he is an Israelite,' replied Samuel. 'he will go and return.'7 While they were sitting he went and returned. [Thereupon] Ablat arose and threw off his [the man's] knapsack, [and] found a snake therein cut up and lying in two pieces — Said Samuel to him, 'What did you do?'8 'Every day we pooled our bread and ate it; but to-day one of us had no bread, and he was ashamed. Said I to them, "I will go and collect [the bread]".9 When I came to him, I pretended to take [bread] from him, so that he should not be ashamed.' 'You have done a good deed,' said he to him. Then Samuel went out and lectured: But charity10 delivereth from death;11 and [this does not mean] from an unnatural death, but from death itself.

Sabbath 156b

All this goes to show that one should not judge a book without reading it first. I do understand that as this author's article was published in 2001, she had not yet seen the further developments of the Potter series, but even in the first book, there are no examples of the kind of witchcraft and sorcery the Torah deplores. Or, if very, very technically there are (based on the Rashi to Devarim) the desire to be wicked is not what draws third-graders to the book. And the "world of Harry" is not antithetical to, and may even supplement, the "world of holiness."

Generalizations are bad on any occassion, but they are

especially bad when one hasn't even read the subject matter in question and is making statements based on the reactions and misunderstandings of third graders. Recall, it was a certain child's

brother who said the Satan warred with God, not J. K. Rowling. And even if the child

had been drawn to some strangely disturbed conclusion, J. K. Rowling is only responsible for the content of her book- not for the way other people choose to view it/ misuse it/ misread it/ misunderstand it.

Read the book in question, and then, if you choose to, pontificate.

But you can hardly attack a fantasy book through the use of generalizations, misunderstandings, ideas engendered by the confusion of children, and the fact that you have refused to read it, lest it taint you.

This is only one example. The reason it stood out was because the article had actually been

published, as opposed to having been an opinion merely spoken aloud. But this kind of idea- opinions turned into facts on the whim of some person- has been used, to very bad effect, at Templars. Perhaps the most infuriating time this happened was during History class, where Mrs. Jellybean happily taught us all the ulterior motives Israel had in creating Yom HaShoa and Yom HaAtzmaut, the fact that Joseph Aaron suffered from various problems during his childhood, which meant his word was not to be trusted, and that any Jew who went to see 'The Passion' was a traitor to his religion because Mel Gibson's father denied the Holocaust. Oh, and that there was no such thing as an Orthodox Jewish Democrat.

Opinions are opinions. Facts are facts. If you are going to state an opinion, make sure you can prove it. Support it with facts. Or, as I could otherwise state it, if you're going to write about a book, make sure you've read the book.